Together, We Can End Unsheltered Homelessness

Unsheltered Homelessness Timeline

1890s

Portland Had the Highest Homelessness in the Nation

Unsheltered homelessness has never been common

Portland's challenges of an exploding population and an affordable housing crisis are not new. From 1890 to 1915, Portland’s population grew from 45,000 to 225,000, a 400% increase in only 25 years.

Homelessness in Portland has been an issue since its earliest days. As a major hub for logging, shipping, agriculture, and a stop-over point for gold rushers, Portland’s rapid urbanization and economic growth in the late 1800s resulted in many skilled and unskilled men searching for work and housing. In fact, by the turn of the century, Portland had more homeless people per capita than any other U.S. city and was the fourth largest in absolute numbers - trailing only Chicago, San Francisco, and New York. *

Although they encountered a scarcity of affordable housing options and were without permanent housing, they rarely slept unsheltered on the streets. At the height of the homeless population, Portland had an abundance of single-room occupancy (SRO) options. These rooms typically consisted of a bed and minimal amenities and offered temporary shelter for both employed and unemployed homeless individuals. Although not perfect living conditions, SROs offered shelter and security during times of economic and housing instability.

*Sawyer, Chris D. From Whitechapel to Old Town: The Life and Death of The Skid Row District, Portland, Oregon. Portland State University, 1985, Ph.D. Dissertation.

1920s

America's Basic Housing Unit Was a Bed, Not a House

An option for every price and person

In the early 20th century, housing was much more flexible, fluid, and communal, especially in the booming cities. A home was not always a house. It was a room in a house, a hotel, or a single room occupancy (SRO), which is a single room with shared bathroom facilities.

“Boarding and lodging so pervaded American family life…in a conservative estimate for these years, 33% to 50% of all urban Americans either boarded or took boarders at some time in their lives.”

Your sleeping options were connected to what you could pay, but there was an option for every price and person. The vast majority of people could keep a roof over their heads.

Today, HomeShare Oregon, ‘Rent a room, create a home,’ is a similar solution to the flexible and low-cost housing that Portland relied upon a century ago to house the workforce that built our city.

1940s

The Evolution of America's Basic Housing Unit

The Birth of the ‘Starter Home’

In the post-World War II construction boom, the concept of a ‘starter home,’ or a single-family home, was born. These starter homes, which were 1,400-square-foot or less, comprised the vast majority of all new construction throughout this period:

New Construction Single Family Homes - 1,400 sq ft or less

-

1940s – 70%

-

2020s – 8%

Since the post-World War II population boom, the construction of small starter homes has plummeted, with homes less than 1,400 square feet making up only 8% of new construction. These homes were an attainable size for people joining the workforce, new families, and retirees, but there are no longer enough to meet the need.

In addition, as the size of single-family homes has increased, the average number of people per household has decreased from 3.6 in the 1940s to 2.4 in the 2020s. Despite the shrinking number of people in our homes, the square footage and our thirst for larger homes have only increased.

1940s

The Evolution of America's Basic Housing Unit

The Birth of the ‘Starter Home’

In the post-World War II construction boom, the concept of a ‘starter home,’ or a single-family home, was born. These starter homes, which were 1,400-square-foot or less, comprised the vast majority of all new construction throughout this period:

New Construction Single Family Homes - 1,400 sq ft or less

-

1940s – 70%

-

2020s – 8%

Since the post-World War II population boom, the construction of small starter homes has plummeted, with homes less than 1,400 square feet making up only 8% of new construction. These homes were an attainable size for people joining the workforce, new families, and retirees, but there are no longer enough to meet the need.

In addition, as the size of single-family homes has increased, the average number of people per household has decreased from 3.6 in the 1940s to 2.4 in the 2020s. Despite the shrinking number of people in our homes, the square footage and our thirst for larger homes have only increased.

Today, in Portland, with a limited stock of houses measuring 1,400 square feet or less, renting a house or homeownership is more expensive and difficult than ever. This is one reason why the number of people without a home is rising.

1960s

The Deinstitutionalization of the Mentally Ill

The number of mentally ill patients living in state hospitals dropped from 535,000 in 1960 to 137,000 in 1980

Deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill has roots in the civil rights and civil liberties movements of the 1960s, which envisioned more fulfilling lives for those who had been languishing in understaffed psychiatric hospitals through new medications and robust community-based services.

However, the rapid closure of many states’ psychiatric hospitals without sufficient community-based resources in place led to a range of unintended consequences, including homelessness, incarceration, and a lack of adequate support for those with severe mental health needs.

The abrupt discharge of patients, many of whom were not equipped to navigate independent living, also contributed to an increase in the population of individuals with mental illnesses in the criminal justice system.

1970s

Cities Began Banning Flexible Housing, Including Single Room Occupancy (SROs) Units

Between the mid-1970s and 1990s, one million SRO units were destroyed, including over 2,400 in Portland.

Single room occupancy (SRO) is a type of low-cost housing typically aimed at residents with low or minimal incomes or single adults who like a minimalist lifestyle who rent small, furnished single rooms with a bed, chair, and sometimes a small desk with a shared bathroom and kitchen.

There was a national movement to tear down the variety of SRO options for various reasons, including but not limited to urban renewal, shifting housing policies, economics, and perception and stigma. As cities began removing and banning single room occupancy units, which provided affordable housing options for low-income individuals and marginalized communities, it left many in the community without stable housing options, leading to an increase in housing insecurity and homelessness.

1980s

The Modern Era of Homelessness Began

Economic downturns, rising housing costs, lack of mental health support, and the decline of affordable housing options contributed to an increase in the homeless population.

In the 1980s, because of the reduction in communal and shared housing, the focus on single family homes, the deinstitutionalization of our mental health system, and many other factors, the modern era of homelessness began in the United States. Today:

-

There are 653,000 homeless persons in the U.S., and 140,000 suffer from severe persistent mental illness (SPMI)

-

There are 6,297 homeless persons in Portland, and

-

3,944 are living unsheltered

The increased visibility of homelessness in urban centers spurred public awareness and prompted various responses from federal, local, and nonprofit governments. Homeless shelters and soup kitchens proliferated, and elected officials and advocacy groups began to push for policy changes to address the root causes of homelessness.

1980s

Permanent Congregate Shelters

Communities Respond to The Modern Era of Homelessness

Permanent congregate shelters emerged as a key component of the broader strategy to address homelessness, providing a place to live and access the resources and support necessary for individuals to rebuild their lives and achieve greater stability.

The 1981 "Right to Shelter" lawsuit, known as Callahan v. Carey, was a landmark case in New York City that established the legal right to shelter be provided to every homeless man, woman, child, and family. It was a pivotal moment in the fight against homelessness, highlighting governments' legal and moral responsibilities to care for New York City’s most vulnerable citizens and laying the groundwork for ongoing efforts to ensure the right to shelter and housing stability.

Congregate Shelter Examples:

New York City

2023 New York City Shelter Statistics:

-

66,195 homeless persons are sheltered per night

-

$3.5 billion homeless shelter budget per year

-

$145.13 per person per night

2022 Percent of Homeless that are Unsheltered:

-

New York City 5%

-

San Francisco 56%

-

Portland 58%

New York City's Right-to-Shelter Mandate for Homelessness Faces New Test Bloomberg Photo

_tiff.png)

San Diego

In December 2017, The Alpha Project’s Bridge Shelter opened in downtown San Diego:

-

200 persons per night

-

24-hour permanent shelter

-

$3 million to setup large tent structure

-

$3 million per year to operate

-

$52.50 per person per night

Lakesha Jones, Manager - Veterans Village Bridge Shelter, 200 souls – 10 women & 190 men

Salt Lake City

In 2020, The Gail Miller Resource Center shelter opened with the Road Home as its operator:

-

300 persons per night

-

24-hour permanent shelter

-

$27 million construction cost

-

Mini police precinct located inside

Mike Young, director of shelter operations for the Road Home, and Sergeant Nathan Meinzer of the Salt Lake City Police Department. Police anonymous survey of shelter residents found that only 1% of respondents felt “Less Safe” because of the community policing presence.

Portland

In 2022, The City / County Joint Office of Homeless Services opens the Market Street Shelter:

-

100 persons per night

-

24-hour permanent shelter

-

Reservation required

-

$4 million operating budget

-

$109.00 per person per night

Market Street Shelter, Portland, Oregon

Portland now has 3,149 permanent shelter beds that cost $62 on average per night, have a two to four week wait list before gaining access and take years to plan and millions to build.

In 1988, Portland’s leaders found a way to deliver safety and security to our unsheltered at a fraction of the cost of a permanent congregate shelter and could be rapidly deployed in months in place of years to meet the humanitarian crisis that plagued our city.

1988

Portland Ended Unsheltered Homelessness

Homelessness in the 80s was endemic to Old Town, Skid Road

Mayor Bud Clark’s mission was to help those experiencing homelessness. He created a shelter network that was flexible and expanded as needed to meet the demands on a daily basis.

He insisted on a balanced approach and believed that all citizens, including those who were unhoused, were entitled to peaceful, respectful living environments. This idea would create an accepted "Community Standard." For example, shop owners could expect that their doorways or sidewalks wouldn’t be used as a bedroom or toilet, and unhoused persons could expect to have a place to toilet and sleep safely.

With the shelter network in place, Mayor Clark and his team were able to keep the city virtually free of campsites. A City of Portland report to the Mayor, released in September 1988, Breaking the Cycle of Homelessness: The Portland Model, summarized the success:

“The emergency shelter system has the capacity to handle those who need it. Anyone who wants emergency shelter can now get it. No one is forced to sleep in the streets.”

This nationally lauded plan, with the goal of keeping the streets clear and open for business, included:

-

The coordination of 65 public and private partnerships

-

Churches that opened emergency shelters at night and were able to have normal operations during the day still

-

10-hour nighttime only non-permanent shelters

-

Rescued SROs that were being edged out by gentrification

-

City-sanctioned trash removal (The program later became Downtown Clean & Safe)

-

Opening the CHIERS Sobering Center

-

Increased services for mental illness and alcohol and drug treatment

The whole plan was implemented in 12 months.

Mayor Clark leads officials (including Commission Mike Lindberg, a Shelter Portland Leadership Council member) on a walking tour of Old Town to see how policies are affecting the neighborhood, Oregonian

Mayor Bud Clark stands in front of Union Station, the centerpiece of a renovation project he says will eliminate Skid Road, Oregonian

Breaking the Cycle of Homelessness states, “Here’s the bottom line: The cycle of homelessness can be broken, and the constant drain of support can stop for those that reach self-sufficiency. Those who cannot reach self-sufficiency can be accommodated in a way that does not detract from the security and comfort of the city’s residents or the vitality of its businesses. The city can be an exciting, growing, livable home for all its citizens.”

Unfortunately, the solutions that were effective in Portland only a few decades ago are no longer being employed and our shop owner’s doorways are once again being used as a bedroom and toilet.

Unsheltered homeless person living in storefront doorway at Northeast 43rd and Sandy Boulevard, Portland

Back to the Future

Today, Shelter Portland is pursuing a similar strategy outlined in ‘Breaking the Cycle of Homelessness: The Portland Model’ to care for our community and end unsheltered homelessness as swiftly as Mayor Clark did in 1988.

(editor’s note: Dan Steffey, the assistant to Mayor Clark and the point person for implementing the mayor’s unsheltered homelessness plan, is currently a special advisor to the Shelter Portland board, and Portland City Commissioner Mike Lindberg, from 1979 until 1996, is a member of the Shelter Portland Leadership Council)

2000s

“Housing First” is Born

An Ideological Shift in Interventions

To address homelessness, many localities and cities in the nation have begun diverting resources from ‘shelter first’ strategies to connect people to permanent housing quickly, ‘Housing First,’ and coupling with supportive services to maximize housing stability. The model was popularized by Sam Tsemberis and Pathways to Housing in New York.

Housing First opposes preconditions or barriers such as sobriety, treatment, or service participation requirements.

Numerous studies show that Housing First participants experience higher levels of housing retention and use fewer emergency and criminal justice services, which produces cost savings in emergency department use, inpatient hospitalizations, and criminal justice system use.

-

More than 75% of households remain housed a year after being rapidly re-housed

-

$31,545 in cost savings per person housed, according to one study.

-

Another study showed that a Housing First program could cost up to $23,000 less per consumer per year than a shelter program.

Considering the deinstitutionalization of our mental health hospitals and systems that began in the 1960s, Housing First has proven successful at addressing the hardest-to-serve chronically homeless population, a substantial number of whom are mentally ill.

Today, in Portland, 72% of people sleeping outside reported a mental illness, chronic physical condition, and/or substance use disorder. Traditional affordable housing is often not enough for those people, and emergency shelter is, at best, a short-term solution.

Examples of Housing First:

Portland

-

The historic Henry Building is a six-story building in downtown

-

SRO - Single Room Occupancy

-

172 Low Barrier Units

-

$37,674,708 total cost to renovate

-

$46.57 cost per person per night with Permanent Supportive Housing

-

PSH per person-per-year costs are estimated at $17,000

Picture of a room at The Henry, SRO, in downtown Portland

Lisbon, Portugal

In 2009, the Portuguese Association for the Study and Psychosocial Integration (AEIPS), after visiting New York’s Pathways to Housing, the originators of the Housing First model, set up fifteen Housing First type units to stabilize and integrate those suffering from severe persistent mental illness (SPMI) into the community. By almost all measures, the program has been a success in housing Lisbon’s chronically homeless persons who suffer from mental illness and other disabilities. Today, AEIPS in Lisbon provides:

-

400 apartments – “Most program participants are seeking privacy – they may be hearing voices or up at night talking”

-

Independent living in the community

-

90% of program members suffer from SPMI

-

60% receive medication to treat their disorder and, in some cases, dependent on behavior, required to maintain housing

-

35% are substance users

-

AEIPS provides case worker and limited cleaning services

-

Psychotic episode with potential harm to self or others results in public safety department transport to public health facility, not jail

A photo of Robert and his case worker Sofia Lewis, in his home in Lisbon. Robert suffers from schizophrenia symptoms and was chronically homeless in Lisbon until AEIPS Housing First assistance.

Robert’s neighborhood. If a Housing First participant is placed in an apartment, AEIPS will limit program participants in any one building to no more than 5% of residents

Teresa Duarte, AEIPS Lisbon Housing First Director, in Robert’s neighborhood, where the community helps look out after him.

2004

‘Home Again’: Portland Turns its Sights on Ending Homelessness

Attempting Before Ending Unsheltered Homelessness

A little over a decade after Mayor Bud Clark and his administration’s success in ending unsheltered homelessness, where anyone who wanted nighttime emergency shelter got it, Portland and Multnomah County turned their sights on a more aggressive goal: ending homelessness. Home Again: A 10-year comprehensive strategy to end homelessness was initiated by Mayor Tom Potter and Multnomah County Chair Diane Linn in response to the growing concern about homelessness in the region.

Adopted by the City Council in 2005, the plan aimed to unite government agencies, non-profit organizations, businesses, and community members to work collaboratively towards ending homelessness within a decade.

The plan was built on three principles:

-

Focus on the most chronically homeless populations

-

Streamline access to existing services to prevent and reduce other homelessness

-

Concentrate resources on programs that offer measurable results

The nine strategic actions identified as instrumental in ending homelessness were inherent in the three principles:

-

Move people into Housing First

-

Stop discharging people into homelessness

-

Improve outreach to homeless people

-

Emphasize permanent solutions

-

Increase the supply of permanent supportive housing

-

Create innovative new partnerships to end homelessness

-

Make the rent assistance system more effective

-

Increase economic opportunity for homeless people

-

Implement new data collection technology throughout the homeless system

Home Again experienced many systemic successes:

-

Opened the ground‐breaking Bud Clark Commons, which includes a day center for housing access and services, nighttime emergency shelter for 90 men, and 130 units of permanent supportive housing.

-

Created the nationally recognized Short‐Term Rent Assistance program (STRA) and consolidated federal, state, and local funding from the City of Portland, City of Gresham, Multnomah County, and Home Forward (Portland’s public housing authority) into a single, centrally administered rent assistance and eviction prevention program.

-

Operators at the 211 info phone service offered quick answers and advice for people who had lost or were at risk of losing their homes.

However, due to various factors, including but not limited to the subprime mortgage crisis, increased migration, rising housing costs, and growing unemployment, ten years later, homelessness was still very much a reality in Portland.

Departing from the principles and successes of Bud Clark’s 12-Point Plan decades earlier, the Home Again plan narrowed its focus to trying to end homelessness and was overwhelmed by the increasing inflow of the unsheltered homeless population.

The 2015 Point-in-Time count identified 1,887 unsheltered homeless people, a 31% increase from the 2007 (1438) Point-in-Time count. Unfortunately, focusing intervention efforts on homelessness did little to stem the tide of the increasing unsheltered homeless population.

2009

The HEARTH Act

The federal government accelerates the shift from Shelter to ‘Housing First’

The Congressional ‘Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing’ (HEARTH) Act helped entrench federal support for Housing First and expand the availability of permanent housing beyond people experiencing chronic (long-term) homelessness to families, youth, and nondisabled, single adults (short-term).

Hearth Act Emphasis:

Before 2012 HEARTH implementation:

-

Shelter focused on providing safety and services for those experiencing a rare, brief, and nonrecurring short term homeless event (often nondisabled).

-

Housing First (Permanent Supportive Housing – PSH) was developed to help those suffering from long term chronic homelessness (often disabled by mental illness, addiction, or physically).

After 2012 HEARTH Provisions go into effect:

-

Housing First was expanded and became a “Whole System Orientation,” which applies to both short-term and long-term homelessness (both nondisabled and disabled).

-

Federal funding for short-term emergency shelter beds is reduced.

In 2014, following the HEARTH Act guidance, the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) encouraged governments to view Housing First as a “whole system orientation,” making Housing First the underlying approach behind every community's response to homelessness, whether a person is healthy, short term houseless, or suffering from addiction, mental illness, or a medical disability and long term homeless.

The HEARTH Act ushered in a period of success (increase in PSH units), missed opportunities (decreased shelter capacity), and left the remaining challenge of skyrocketing unsheltered homeless.

Today, the federal government’s portion of Portland and Multnomah County Joint Office of Homeless Services annual budget is minimal (7%). Portland needs a solution tailored not by federal policy, but by local disaster recovery needs. A program that is paid for by Portland and tailored to care specifically for Portlanders to end unsheltered homelessness and the suffering of both the unhoused and housed in our community. Permanently housing our homeless is the goal, but it won’t shelter Portland’s skyrocketing unsheltered population today. With a five-year housing waitlist, our city and county has normalized homeless encampments and asks our houseless neighbors to wait outside in unsafe, unsanitary, and dangerous conditions.

Trevor's Story

Trevor, who is from Seattle and now lives on the I-405 Multi-Use Path (MUP), is one of 3,944 unsheltered persons who will sleep on our streets tonight. Trevor suffers from addiction and mental illness. He has a loving family and a home to go to.

John, Trevor’s father, was terrified for his son’s safety. He built a mobile housing unit outfitted with caster wheels to allow Trevor to roll it down the MUP to another spot each time he receives a posting notice of an impending camp cleanup. Absent basic shelter provided by the city or county, which in turn fosters Trevor’s camping behavior, John feels he must do something to care for his son.

Trevor’s mobile homeless shack on the Multi Use Path in Portland’s Lents Neighborhood

Message from Trevor to his dad, John

Before we can house our homeless, we must shelter our unsheltered, or stories like Trevor and John will multiply, and the suffering that our community is experiencing will only grow.

201os

Built for Zero

A System for Ending Homelessness, After Ending Unsheltered Homelessness

Homelessness is a complex, life-threatening problem. It can be solved — but only if systems are coordinated to reduce and end it continually, which can be accomplished only after you have ended unsheltered homelessness.

In 1990, Rosanne Haggerty founded Common Ground Community, which created nearly 3,000 affordable homes in New York City, many with permanent supportive housing services. Though these buildings ended homelessness for its tenants, overall homelessness in the city continued to rise.

Then, in 2011, she founded Community Solutions to employ a Housing First strategy at scale and led the 100,000 Homes campaign. Participating communities house more than 105,000 Americans, but no community ends homelessness. Housing First, on its own, was not ending homelessness.

In 2015, Community Solutions launched the Built for Zero initiative to learn what it takes to not only house more people but also drive overall homelessness down to ‘functional zero.’

The first step to solving homelessness is having a shared definition of what we are trying to achieve. Communities in Built for Zero use functional zero, a milestone that indicates that homelessness is measurably rare and brief for a population. They often work to achieve functional zero for one target population at a time (e.g., ending veteran homelessness and then moving on to another population, e.g., youth homelessness, until homelessness for all populations are ended [other populations include chronic, family, and elderly]) as steps on the way to making homelessness rare and brief for everyone. This dynamic milestone enables communities to confirm whether they continuously drive homelessness toward zero.

Today, 14 Built for Zero communities have ended veteran and/or chronic homelessness.

But with skyrocketing unsheltered homelessness in Portland, ending unsheltered homelessness and providing for the unmet basic need of a roof over every Portlander is our most important first target population.

Once Portland’s unsheltered homeless population and inflow are reduced to functional zero, the next immediate step is reaching functional zero for a specific chosen sheltered homeless target population.

Built for Zero best practices indicate that starting with the smallest target population and swarming and solving is best. Show our community that we can achieve. If there are 114 elderly adults aged 70+ (2022 Multnomah County Point in Time count), then focus on ending homelessness with this one population. Achieve, CELEBRATE the win with the entire City of Portland, hold onto the win, and then target the next population. Everyone loves a winner. Portland desperately needs a win.

Shelter Portland has visited, toured, and conducted best practices discussions with three communities ending veteran and/or chronic homelessness. The common denominator is that all three ended the unsheltered homelessness (reached functional zero) population first:

Rockford, Illinois

Angie Walker, Homeless Program Coordinator at City of Rockford Human Service, and Keith Wilson, Shelter Portland, in Rockford, Illinois

Angie and Keith spending the day in Rockford providing outreach to homeless folks.

How did they reach functional zero for unsheltered, veterans, and chronic homelessness:

-

Rockford's mayor personally engaged large property owners to provide housing

-

Fire, Police & Mayor - Befriending each homeless person and addressing a person's needs

-

Two churches offer shelter in winter - At zero cost to the county

-

Emergency shelters now have open beds every night

How did they reach functional zero for unsheltered, veterans, and chronic homelessness:

-

Hospitals no longer “Discharge to Homeless”

-

One police officer met two homeless persons arriving at the bus stop and immediately helped them get back home

-

Police officers uphold codes and work with Open Doors Homeless Coalition to provide for an individual’s specific needs:

-

“I want to help.”

-

“What does that look like?”

-

“But you can’t camp here.”

-

-

Opinion: We can end unsheltered homelessness in Portland

Bergen County, New Jersey

Shelter provides medical treatment for the unhoused

How did they reach functional zero for unsheltered, veterans, and chronic homelessness:

-

Homelessness is considered a ‘DISASTER RELIEF,’ and any person living on the street is immediately cared for and provided shelter and services

-

Long-term resources for county residents only

-

Focus on ‘reunification’ – Connecting the unhoused with their social network, either friends or families.

-

Bergen’s nighttime emergency shelter guests flow into their 24-hour shelter, which requires engagement and a stay limit of 90 days to provide housing as the next step. Portland is the reverse; 24-hour shelters require no engagement and have little or no stay limitations, with many guests being sheltered for more than a year.

-

Bergen’s Nighttime emergency shelters have been closed as homelessness is reduced

Keith Wilson, Shelter Portland, meeting with Trinette Crump, Open Doors Homeless Coalition Outreach Program Manager, and Mary Simons, Executive Director, in Gulfport, MS, to review county homeless best practices and how they achieved functional zero for veterans and chronic homelessness.

Mary Sunden, Executive Director, CCCDC Shelter Operator, Keith Wilson, Shelter Portland, and Julia Orlando, Director, Bergen County Housing, Health and Human Services Center

These three extraordinary communities have proven that homelessness can be ended, but we must END UNSHELTERED HOMELESSNESS FIRST!

201os

New Orleans Mayor's Challenge

Ending Unsheltered Homelessness

New Orleans, with unsheltered homeless at nearly twice the level of Portland, housed 86% of their unsheltered in 24 months. To find out how Shelter Portland traveled to New Orleans, met with Unity of Greater New Orleans, its homeless services coordinator, and stakeholders, and then, after this visit, had two conversations with former Mayor Mitch Landrieu to find out how they quickly and humanely housed their unsheltered.

President Biden’s White House Advisor and former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu and Shelter Portland Keith Wilson

In August of 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana, and the following day, 250,000 residents were homeless. In 2008, when FEMA ended its emergency support, homelessness skyrocketed, and no city was more impacted than New Orleans. In 2010, newly elected Mayor Mitch Landrieu and his team went to work. They immediately employed a ‘disaster recovery’ mindset and rallied local, regional, and federal resources. He and his team began personally working with each stakeholder and established clear objectives. By 2013, the vast majority of New Orleans’ unsheltered were sheltered and housed. New Orleans reduced unsheltered homelessness from 7,385 to 1,039 in only two years.

By comparison, Portland, without a ‘disaster recovery’ mindset, is experiencing skyrocketing unsheltered homelessness, which has increased 136% from 2017 to 2022.

In 2014, after significantly reducing unsheltered homelessness, Mayor Landrieu accepted the White House’s Mayor's Challenge to End Veteran Homelessness. When he first outlined to his homeless service providers his expectations of housing their veteran homeless population within 24 months, he was told that “it can’t be done!”

Undeterred, he challenged them to innovate. He promised them that his administration would provide the necessary support. In the subsequent meeting, when these stakeholders agreed they could achieve the mayor’s objectives, he was pleased and notified them that they needed to reach them in only half the time. First, he wanted them to believe. Second, he needed them to trust him that his administration would provide the promised support. And incredibly, working together, they met and exceeded the mayor’s objective and their community’s needs, and they ended veterans’ homelessness in 12 months.

Today, New Orleans has only 364 unsheltered homeless people. Perhaps Mayor Landrieu and his team, along with the Unity of Greater New Orleans homeless service agency, have the greatest legacy of their community’s ability to sustain this disaster recovery mindset years after the actual disaster had passed. New Orleans shows us that Portland can end unsheltered homelessness. The crisis on our streets is not so large that we cannot quickly and humanely care for our most vulnerable neighbors. Yes, unsheltered homelessness can be ended. But we must change our mindset from business as usual to one focused on ‘disaster recovery.’ By caring for our unsheltered homeless, we are caring for all Portlanders – our homeless, housed residents, and small and large business owners – and we begin to restore livability and community safety. But only when we stop making excuses and saying, “It can’t be done!”

2012

Anderson v. The City of Portland

Homeless Protections and Camping Ban Confusion Escalate

As Portland slowly moved away from Mayor Bud Clark’s 1988 success of relying on a network of public-private partnerships to provide walk-in nighttime emergency shelters for anyone who wanted it, by 2008, with shelter space no longer available for all homeless people, tent camping throughout Portland began to increase.

City government, law enforcement, and homeless service providers disagreed on how to deal with this crisis. The contrasting goals of all the stakeholders resulted in a lawsuit that would have a lasting effect on how Portland handled the increasingly unsheltered homeless population.

Anderson v. The City of Portland was a class-action lawsuit filed in 2008 by homeless individuals against the city of Portland. The lawsuit challenged the city's practice of seizing and destroying homeless individuals' property without proper notice or opportunity to reclaim it. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, stating that the city's actions violated the Fourth Amendment's protection against unreasonable search and seizure.

In 2012, the city settled the case, resulting in the city of Portland revising its policies regarding the disposal of homeless individuals' property. The ruling had specific policy changes in how Portland could interact with the unsheltered homeless population:

-

Campers must be given notice at least 24 hours* and not more than 7 days before a camp is cleared

-

Confiscated property must be held for at least 30 days

-

Agencies must take photos and keep a list of confiscated property, although backpacks may not be opened.

-

Campsites must be videotaped after items have been confiscated

-

Campers will not be moved at night unless an emergency requires it

This led to changes in how city officials interacted with homeless camps and how they handled the belongings of those experiencing homelessness.

The case brought attention to the rights of homeless individuals and the need for cities to respect those rights, including property rights. It highlighted the importance of treating homelessness as a social issue that required humane and legally sound solutions rather than simply a law enforcement matter.

The ruling clearly intended to give added protection to the unsheltered homeless population when shelters were at capacity. However, it led to mass confusion about where people could and could not sleep. Law enforcement’s role in enforcing city codes became murkier, and they almost completely withdrew from enforcing even the daytime camping bans. Other city groups interceded to offer aid, but the inconsistent leadership and lack of a clear policy resulted in an explosion of encampments across the city.

*In 2021, the 24-hour policy was changed to 72 hours. See Timeline 2021.

2012

‘A Home For Everyone’:

City and County Convene and Collaborate to End Homelessness

Attempting Before Ending Unsheltered Homelessness

In 2012, the City of Portland, Multnomah County, and Home Forward convened a new committee that brought together diverse stakeholders to review data, listen to the community, and learn from effective practices locally and nationally. This group created “A Home for Everyone” (AHFE) with the vision that “No one should be homeless—everyone needs a safe, stable place to call home.”

This sweeping collaboration of government and nonprofits, the faith community, philanthropy, and businesses focused on a ‘continuum’ of services, including nighttime emergency shelter and transitional housing. It also focused on long-term solutions to homelessness, including permanent housing and robust prevention services—rent assistance, affordable rental housing, and supportive housing.

2015

Portland City Council Declares

Homeless Emergency

Some Homelessness Statistics Show Improvement

While A Home For Everyone (AHFE) increased nighttime emergency shelter from 2013 to 2015, overall homelessness increased by 4%.

Then, In August 2015, AHFE received a startling figure. The number of people using temporary shelters had soared by 42 percent over the previous year. Coupling that with a 30-percent rise in rental rates over five years—and by some accounts, a 15-percent rise in 2015 alone—AHFE decided that drastic and immediate action was necessary to stay on track to meet their goal.

In October 2015, Mayor Charlie Hales declared a homeless emergency and coordinated with Multnomah County to develop an immediate response. With a $30 million pledge—$10 million from the county and $20 million from the city—the new investment intended to fund more shelter beds for women and families, new affordable housing units, and housing for people facing mental health issues. Also funded were protections for people facing housing instability because the cost of rent was skyrocketing at the time.

This gave the city power to waive land-use restrictions so they could convert existing buildings into emergency shelter spaces and start the construction of more permanent affordable housing. From 2015 to 2017, nighttime emergency shelters increased from 1,914 to 2,509, and unsheltered homelessness decreased for the first time in seven years.

Since 2015, the declaration has been extended five times and is currently in effect through March 22nd, 2025. During that time, Portland has invested $1.7 billion in specific programs along the affordable housing and homeless services continuum, and unsheltered homelessness is at the highest level Portland has ever experienced.

2016

Portland ‘Safe Sleep’ Policy

Allows Homeless Camping

Policy Discontinued Six Months Later

In February 2016, Mayor Charlie Hales, soon after declaring the homeless emergency and before the rapid expansion of shelters envisioned in the declaration, implemented a ‘safe sleep’ policy to allow outdoor camps and overnight tent camping in certain locations. The plan was to be evaluated in six months.

The controversial policy ended in August, six months after it was enacted.

Mayor Hales said that the policy did not legalize camping in Portland. Still, without enough shelter beds available for the unsheltered, whether with the policy or not, the city lives in ambiguity until Portland has enough shelter beds.

Regarding the 2015 homeless emergency and the 2016 ‘safe sleep’ policy, neither of these events would have been necessary if Portland sheltered the unsheltered. Portland accomplished this in 1988 and throughout the 1990s. We can accomplish it today to ensure that no Portlander sleeps on our streets in unsafe, unsanitary, and dangerous conditions.

2016

Do Good Multnomah

A Need for Walk-In Nighttime Emergency Shelter Fulfilled

Chris Aiosa, founder of Do Good Multnomah, a Portland-based homeless services provider, recognized the need for additional shelter in Portland and opened a walk-in nighttime emergency shelter at Portsmouth Union Church in North Portland.

Portsmouth Union Church nighttime emergency shelter

Do Good converted Charles Jordan Community Center to an emergency shelter in 72 hours during the COVID disaster emergency

When the Covid pandemic emerged, and within 72 hours of receiving a request for assistance from the City / County Joint Office of Homeless Services (JOHS), he closed his Portsmouth Union Church shelter and opened a large congregate 24-hour emergency shelter using the Charles Jordan Community Center

His experience, along with the help of Andy Goebel, his operations manager, and this example shows that shelters using existing unused spaces can provide low-cost and immediate shelter for those suffering from unsheltered homelessness.

Chris and Andy’s experience with rapidly setting up a large shelter and as board members of Shelter Portland has been invaluable as Shelter Portland has developed its blueprint to end unsheltered homelessness in Portland.

2016

Joint Office Of Homeless Services

Portland’s Unsheltered Homelessness Begins to Skyrocket

The City/County Joint Office of Homeless Services (JOHS), formed in 2016, coordinates local, state, and federal funding to address the homelessness crisis in Portland and Multnomah County. Although receiving funding from the city, this new agency is managed by Multnomah County.

Before the city and county founded the JOHS, the city was responsible for funding and managing nighttime emergency shelters for single adults.

Generally, the city-funded shelters were only open at night and closed during the day. In some cases, sobriety, work, a stay based on engagement in services, or limited length of stay were required.

However, the JOHS applying the USICH Housing First approach to addressing homelessness began converting Portland’s shelter system to the Housing First shelter guidelines, “The Five Keys to Effective Emergency Shelter.” Most notably, in 2017, JOHS began converting the City of Portland shelters from nighttime to 24/7 operations. Walk-in access was discontinued and replaced with a reservation or referral-only access system, and all stay and engagement requirements were removed.

Shelters previously receiving funding from Portland and now receiving funding from JOHS and not meeting these new requirements were closed.

Salvation Army Female Emergency Shelter & Housing: CLOSED

On January 23, 2019, the Multnomah County Point In Time count identified 2,037 homeless living unsheltered in Portland and Multnomah County, a 22 percent increase from the previous Point in Time count.

On February 12, 2019, the Portland city council extended the Housing and Homelessness Emergency declaration.

On June 18, 2019, The Joint Office of Homeless Services pulled funding for the Salvation Army Female Emergency (S.A.F.E.) Shelter. Without this funding, the shelter, which has 91 beds of nighttime emergency shelter and 35 SRO apartments, must close.

This lifesaving nighttime emergency shelter and housing, since 2008, located at 2nd and Burnside, was in the heart of downtown, where many of our most vulnerable Portlanders live. S.A.F.E. Shelter provides two levels of housing to meet their client’s needs at any stage of their homelessness journey.

S.A.F.E. Shelter by the Numbers

Total Beds = 126

Nighttime Emergency Shelter – 91 total beds

-

Open 7 PM and closed at 8 AM

-

10 beds for domestic violence victims and reserved for Portland Police drop off

-

46 low barrier walk-in access beds

-

35 low barrier reserved beds with case management

-

Showers and laundry

-

$1.7 million operating cost

Apartments - Deeply Affordable Housing

-

35 Single Room Occupancy (SRO) units

-

Clean and sober with case management

-

Shared bathroom, showers, kitchen, laundry, & community room

-

$395 per room per month rent

-

Self-sufficient and no city funding used to operate

Our daughters, mothers, grandmothers, and those identifying as women need our help now. Pictured are Justin Moshkowski, Keith, and Major Bob Lloyd. Justin and Bob are with the Salvation Army.

Major Lloyd, Kristi Delagarza, and Keith outside of the front door at the S.A.F.E. shelter entrance on 2nd Avenue.

Today, unsheltered homeless camping next to the empty Salvation Army shelter on Burnside.

In 2008, An Oregonian file photo of the opening of the Salvation Army Female Emergency Shelter in downtown Portland. LC- THE OREGONIAN

Today, 35 SRO apartments sit empty during a housing crisis.

While standing with Scott Kerman, the executive director of Blanchet House, and greeting homeless souls arriving for breakfast, Keith Wilson, Shelter Portland, first saw and learned about L.B.’s story. With the SAFE shelter only a few blocks away, Shelter Portland is committed to reopening this important shelter. Oregonian Beth Nakamura

In 2019, there were 1,394 homeless females. 27 of them died. The S.A.F.E. Shelter would have provided safety for 126 of them, but it was closed when every effort should have been made to keep it open.

The need and suffering on our streets are horrendous. The Oregonian article about “LB” who sits at the foot of the Blanchet House daily, only a matter of blocks from the closed S.A.F.E. Shelter, highlights how important this lost resource was then and NOW.

In the 1990s, when Mayor Bud Clark and Commissioner Mike Lindberg were ending unsheltered homelessness, they partnered with organizations to open shelters and prevent SROs from closing. Incredibly, in 2019, during the middle of a housing and homelessness emergency, our city and county leaders were closing ours.

The same debate continues today:

Bybee Lakes Hope Center Shelter: “VERGE OF CLOSING”

On October 2, 2020, The Bybee Lakes Hope Center opened. For three years, this facility has been funded with no public support from the City of Portland or Multnomah County.

Bybee Lakes, Portland’s largest shelter, has a capacity of 318 residents and requires long-term program participants to be clean and sober. This requirement does not meet the Joint Office of Homeless Service Housing First shelter guidelines, and funding has been denied for the past three years. Only recently was funding made available from the county to help keep 175 beds open. However, funding was only awarded to keep the facility operating for a few months.

Bybee Lakes Hope Center Shelter by the Numbers

-

Community-initiated and funded shelter

-

Land and buildings donated

-

318 persons per night capacity

-

30 low-barrier emergency shelter – No clean & sober requirement

-

288 clean and sober resident capacity

-

Adults and families welcome

-

175 current capacity

-

143 empty and unfunded beds ready to help shelter our unsheltered

-

-

-

24-hour permanent shelter

-

Access

-

Emergency Shelter – Walk-In

-

Clean & Sober Program - Reservation and referral

-

-

$32 per person per day

The city’s homelessness emergency, created to “cut much of the bureaucratic red tape that usually accompanies the creation of homeless shelters” and passed by every city council since 2015, was only a red herring.

The 126 beds at the S.A.F.S. Shelter, the 143 beds at the Bybee Lakes Hope Center, and many more trauma-informed facilities throughout Portland sit idle because they did not score enough points on a funding application; specifically, they were only open at night or were not a fully low-barrier program.

JOHS Discontinues Walk-In

Nighttime Emergency Shelters

Shelter Bed Utilization – System Waste Review

Because JOHS changed Portland’s walk-in shelters to reservation-based only and then mismanaged this lifesaving resource, Portland now has one of the nation's worst shelter bed utilization rates. For example, on one of the coldest nights in January 2023, some 796 beds went unused, a 75% shelter bed utilization (2,353 sheltered persons vs 3,149 shelter beds available). By comparison, in the Road Home Homeless System in Salt Lake City (SLC), nearly every shelter bed is occupied every night.

Shelter Bed Utilization Rate:

SLC is different than JOHS in two critical ways.

Like JOHS, SLC uses the same homeless coordinated entry process, but they employ the system at each shelter entry point, which allows for walk-ins. This process removes the possibility of any unused shelter beds that may occur when an outreach worker has processed a reservation and a homeless person does not show up at the shelter to claim their bed

Salt Lake City walk-in nighttime emergency shelter, Shelter Portland’s Mark Johnston and Keith Wilson, and SLC the Road Home’s Amanda Kaluza and Mike Young

JOHS does not require its emergency shelter beds to be occupied; SLC does. Unlike JOHS, SLC conducts nightly bed checks to ensure this critical lifesaving resource is being utilized. In SLC, if a bed is not occupied in two out of three-bed checks, the bed is marked available and provided to a new guest the next night. In Portland, beds are assigned and then not required to be slept in, allowing a person to access meals, showers, and laundry while, in some cases, living in a tent:

Elizabeth’s Story

“My neighbor’s daughter, Elizabeth, grew up across the street but now lives at and around the Greyhound Shelter near Union Station in downtown Portland. She is caught in the middle of her addiction and the dysfunctional relationship between Portland and Multnomah County.

She lives at both the shelter and in a tent nearby. Periodically, she will stay at the shelter to access safety, food, laundry, and sleep. The shelter requires a weekly check-in with her case worker, but other than that, there are few, if any, stay or engagement requirements. When Elizabeth is staying in her tent, she can use drugs freely and is surrounded by her community with ready access to the drugs that fuel her addiction. Still, she is also exposed to the dangers of overdose, abuse, and other unspeakable realities. These are especially severe for a woman living unsheltered.

The City of Portland periodically sweeps her tent. Then, a county outreach worker, shelter, or day shelter quickly provides her with a new tent.

In Elizabeth's case, this cycle has continued for years, and hundreds of Portlanders like her. What reason has our city or county provided her to change this behavior when they are the ones who have fostered and then normalized it?” - Keith Wilson, Shelter Portland Founder and Chair

JOHS has unwittingly set up a non-flexible system that now refuses access, even when beds are empty, to life-saving shelter for some of our most vulnerable citizens:

“I was working with a lady in a wheelchair; she was elderly with no mobility, and she was swept and told to go to a shelter. When she arrived, the shelter told her they couldn’t let her in without a referral.”

Nighttime versus 24-Hour Emergency Shelter

Philadelphia and Portland Comparison

In 2017, JOHS converted Portland’s emergency shelters from nighttime only to 24-hour shelters, while Philadelphia did not. Most emergency shelters in Philadelphia are nighttime shelters, closed during the day.

Essentially, JOHS tripled each shelter's hours of operations and costs without adding one shelter bed.

“There is no regulatory requirement from HUD or any other federal agency that shelters must operate 24/7. The cost of doing so is understandably very expensive. It requires three 8-hour shifts rather than one.”

-Mark Johnston, appointed President Obama’s HUD Assistant Secretary to Reduce Homelessness and Shelter Portland Leadership Council Member.

This change and others contributed to Portland’s skyrocketing unsheltered homeless rate, which increased by 132%. By comparison, unsheltered homelessness in Philadelphia plummeted, decreasing by 27%. The main difference is that Portland shifted to the new USICH Housing First Shelter Guidelines, while Philadelphia did not.

This prolonged underinvestment, reduction in shelter capacity, and change in shelter guidelines have resulted in Portland with the highest unsheltered rate in the nation, except for six cities in California.

35% of Homeless Persons Are ‘Homeless Upon Arrival’

Portland has one of the highest, 'Homeless Upon Arrival' inflow rates in the nation

‘Homeless Upon Arrival,’ an individual who was homeless outside of Multnomah County and voluntarily or involuntarily relocated to be homeless in Multnomah County.

The City of Portland and Multnomah County, in the worst homelessness crisis we have ever experienced, hands out tents instead of providing lifesaving, basic, low-cost nighttime emergency shelter. This, among many other factors, has contributed to Multnomah County having one of the highest unsheltered homelessness rate in the nation, but also the distinction of having one of the highest ‘Homeless Upon Arrival’ rates. Today, 35% of those who are homeless in Multnomah County are ‘homeless upon arrival.’

21% of Multnomah County’s homeless population are both “Homeless Upon Arrival” and from “Outside of Oregon.”

Multnomah County 2022 Point-In-Time Count, Page 74. Of those surveyed, 486 are from Outside of Oregon: Washington or California 192; Other parts of the U.S. 271; Outside of the U.S. 23. (Clark County, Washington, adjacent to Multnomah County, is not considered “Outside of Oregon”)

Portland also has the highest ‘Homeless Upon Arrival’ of those from “Out of State” compared to the other large West Coast cities and possibly the United States.

Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count 2019 Results, LAHSA, Page 24; San Francisco Homeless Count & Survey Comprehensive Report 2019, Page 18; Oakland, Everyone Counts! Homeless Count and Survey, Page 22; Seattle/King County Count Us In, Page 29

Since its Inception, JOHS Has Delivered Devastating Results

Just before the City / County Joint Office of Homeless Services (JOHS) inception, Portland’s 2017 homeless count showed a decline in the number of people sleeping outside. For the first time since 2005, it counted more people in emergency shelters than living outdoors.

However, since 2017, the first year that JOHS took over management of Portland’s shelter system, the results of changes they implemented have had a devastating effect on Portland’s homelessness crisis and have resulted in not only a humanitarian crisis on the streets but also a deterioration of our cities livability and communities’ quality of life, for both the housed and unhoused.

In 2023, JOHS sheltered 156 fewer people than in 2017, the year they began. Because of this poor performance, 2,276 more people became unsheltered and lived on our streets in unsafe, unsanitary, and dangerous conditions. This is despite JOHS’ annual budget growing by $183 million. These devastating results can be measured in lost lives.

Review of deaths among people experiencing homelessness in Multnomah County, Domicile Unknown report

Amid Portland’s worst unsheltered homelessness crisis, with approximately 4,000 Portlanders sleeping on the streets, with an estimated 400 of them that will die, and a shelter system with nearly 800 empty beds, it is unconscionable our city leaders allow this inflexible and inefficient system to continue without taking action.

2018

Agape Village

Faith-Based Communities Add Transitional Housing Capacity

In 2016, Matt Huff, pastor of the Central Church of Nazarene in southeast Portland, embarked on a journey to understand better the community they serve.

The result: in 2018, Agape Village, a tiny home village, was constructed on the property of the Central Church of Nazarene. Construction was done with volunteers from Cascadia Clusters, Agape Blitz, Union Gospel Mission, Central Nazarene Church, Tivnu, and many other youth groups, schools, churches, and organizations from around the Portland area and throughout the country.

Agape Village welcomed its first group of villagers in December 2019. Since then, it has added staff and services and even partnered with Nexus Church in Beaverton to help open a single-family shelter on its property.

Agape Village by the Numbers

-

15 total units

-

8 units occupied on average

-

$235,000 annual operating budget

-

$43 per person per day when at full capacity

Matt Huff, the Executive Director of Agape Village, is also the Executive Director of Shelter Portland

Incredibly, this alternative shelter is only partially occupied. On any night, the surrounding community has dozens, if not hundreds, living in tents and RVs.

This is the same at the Kenton Women’s Village in north Portland, where sleeping pods are often underutilized. For example, in June 2022, only 4 of 16 units were utilized, or 25% occupancy.

Kenton Women’s Village

Because Portland has normalized camping, it is underutilized even when lifesaving shelter is available and nearby.

2018

United Nations Special Envoy Offers Perspective

“There’s a CRUELTY here that I don’t think I’ve seen.”

Leilani Farha, the UN special rapporteur on adequate housing, said on a visit to San Francisco and Los Angeles that ‘unacceptable’ squalor amid US wealth violates rights law. “There’s a cruelty here that I don’t think I’ve seen,” with conditions that do not meet standards set for refugee camps.

Portland’s Cruelty

People living in squalor in downtown Portland underneath Ned Flanders Crossing over I-405, May 2024

Tents next to Ned Flanders Crossing

Leif Spencer with Northwest Community Conservancy at the Ned Flanders Crossing with Jonathan and Jessie. Suffering from “bugs,” Leif arranged for a decontamination shower, a new set of clothes, and a conversation with a shelter intake caseworker.

To better understand the differences between the squalor and cruelty Portland’s unsheltered homeless are living in compared to a refugee camp, Shelter Portland traveled to Athens, Greece, and toured three large refugee camps housing people fleeing war, famine, and persecution from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, and others.

Athens Refugee Camps

Skaramangas, Elaionas, and Schisto refugee camps are located on the outskirts of Athens, a city roughly the same size as Portland. With about 2,000 people each, these camps care for a small fraction of the 250,000 refugees throughout Greece.

The European Union pays Greece approximately $5,000 per person per year ($10 million per camp) to care for these souls while a longer-term solution is being discussed.

While living in Greece, one of the poorest countries in the European Union, these refugees can come and go freely from their camps. However, they have little opportunity with travel and work restrictions within Europe. The citizens of Athens generally stand in “solidarity with the refugees,” but in interviews with Athenians, they see these camps as “cemeteries of souls.”

Each refugee camp visited was relatively clean, organized, and habitable. While not ideal living conditions, these camps do not show the signs of unacceptable squalor and cruelty displayed throughout Portland, confirming the United Nations Leilani Farha’s assessment about the failure of Portland’s leadership and failed policies denying basic human rights for its community members.

Elaionas refugee camp, Athens, Greece,

June 2021

Unlike Portland, Athens has very little noticeable homelessness on cross-town trips from one refugee camp to another. Asking our tour guide how many residents in Athens are homeless, he said, after a long pause, “a few dozen, maybe.” He noted that because every community has a ‘house of peace,’ it was really not possible to be homeless. There was a ‘house of peace’ in most neighborhoods. These benevolent organizations, most often connected with the Greek Orthodox church, provided help for the indigent and elderly. Most provided meals, and many provided nighttime emergency shelter and subsidized housing for their most vulnerable and elderly citizens. The shelter was not only provided for Athenians but in many cases, refugees were also sheltered.

Athens homeless resident. When taking this picture, three shopkeepers in the adjacent stores protested and noted they were caring for this person, presumably suffering from mental illness. After touring Athens for five days, this was the only visible sign of a homeless person.

Portland is not too big to end unsheltered homelessness. If one of the poorest cities in Europe, considered the cradle of civilization, can care for its most vulnerable, Portland can, too.

2018

Martin v. City of Boise & Grants Pass v. Johnson

Landmark Federal Court Cases Clarify Homelessness Rights

The law states: Shelter beds must match the number of unsheltered homeless persons in the community, or camping codes cannot be enforced

In 2018, the 9th Circuit Court, in its ruling of Martin v. City of Boise, citing the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against “cruel and unusual punishment,” stated that the government, City of Boise, cannot criminally punish people for sleeping in public if its homeless population outnumbers available shelter beds.

Subsequently, in 2020, a Grants Pass case further restricted municipalities from enforcing their no-camping bans during the day and stopped them from enforcing the rules at night.

After losing this no-camping lawsuit and subsequent appeals, Boise Mayor Dave Bieter (Shelter Portland Leadership Council member) was determined to comply with the spirit of the law and challenged his community to ensure that every citizen would be provided basic shelter so that no one would be living outside.

He provided this extraordinary leadership example and an account of what happens when a community comes together to end unsheltered homelessness:

“Soon after the case was decided, there was a 120-person tent encampment near my offices at City Hall. My team and community thought that because we lost the lawsuit, camping was now allowed in our city. I explained to my team that, despite the ruling, camping is inhumane, not legal, and nobody should have to sleep on our streets. I instructed my team that we were going to care for these individuals and to prepare 120 shelter beds for the campers, even if overflow beds were needed. After providing 30 days’ notice to this community and outreach services throughout the countdown, we closed the camp.

In an after-action review, we were surprised to find that 40 of these individuals went back home regionally, for example, Cheyenne, Salt Lake City, Portland, etc.; 40 went home locally, staying with family and friends; and 40 accepted our offer of shelter.

My biggest takeaway is that when you normalize camping in your community, it draws people not only from the sheltered homeless and the housed locally, but regionally as well. I thought, incorrectly, if we had more programs for the homeless, we would draw more homeless, but it is the lack of rules and allowing camping that draw people from the housed and from out of town.”

- Boise Mayor Dave Bieter

A story about one of the 80 people camping at Portland’s Laurelhurst Park encampment confirms Mayor Bieter’s point about drawing people who are housed locally and who voluntarily choose to live in a tent if allowed:

“Others choose to camp at Laurelhurst Park because they are seeking freedom. A 32-year-old, who declined to share his name because he didn’t want his parents to know where he was, said he lives outside because he doesn’t trust banks, doesn’t want to work and doesn’t want to pay rent. He has a college degree and a family home he could return to, but he doesn’t want to operate under any rules, he said.”

- Oregonian, May 16, 2021, ‘Where else would they go? Portland standoff with homeless campers at Laurelhurst Park dramatizes personal and political costs of inaction’

Portland fosters this behavior because it does not provide basic lifesaving shelter, which would enable our no-camping laws to be enforced. The city is then forced to allow camping, and this is only made worse by Multnomah County, which, as a normal practice, hands out tents to those who need them or, in the example above, do not need them.

To this day, unlike Portland, the City of Boise ensures that any person who requests a shelter bed is provided with one. Their shelters never turn a person in crisis away. In turn, Boise has no tent encampments.

As Portland Mayor Bud Clark and Commissioner Mike Lindberg ensured in the 1990s, Boise Mayor Bieter was determined to maintain a “Community Standard.” Shop owners and residents are just as entitled to expect that their doorways or sidewalks are free from being used as bedrooms or toilets as an unhoused person is to have a place to toilet as well as sleep safely and protected from the elements.

Because Boise provides shelter for any person in need, their community safety laws (no camping, vehicle licensing, sanitation) are always enforced.

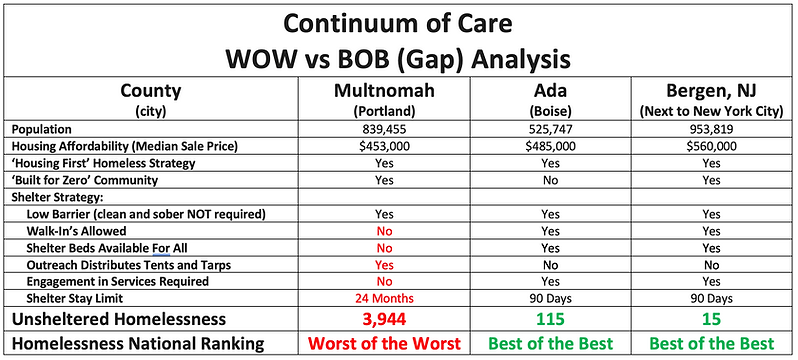

Boise provides basic shelter to every community member in need, unlike Portland, Seattle, and Sacramento, its nearest large West Coast cities. As a result, Boise has one of the lowest unsheltered homelessness rates in the nation. In addition, Boise is now, like Portland once was, one of the most livable cities and best places in the U.S.

Unsheltered Homeless Rates Compared to Adjacent Large Cities

As a desirable location to live, Boise has increased home values faster, a sign of a vibrant and livable city.

Housing Affordability Median Home Sale Price

(County Data)

Keith Wilson, Shelter Portland, and former Boise Mayor Dave Bieter, Shelter Portland Leadership Council member, meeting to work on the blueprint to end unsheltered homelessness in Portland, March 2024

2020

Metro Supportive Housing Services (SHS) Tax

Portland Area Voters Approve Homelessness Tax

In May 2020, voters in greater Portland approved a new regional supportive housing tax. Beginning in 2021 and extending to 2030, its goal is to generate $250 million annually. According to recent projections, it has exceeded expectations and could outperform by $1 billion over the next six years.

JOHS is now one of the nation's most well-resourced homeless services jurisdictions.

However, outcomes for the three Portland metro counties since these funds began to flow to address homelessness are starkly different. In Portland, despite increasing funding to address homelessness, unsheltered homelessness continues to skyrocket.

This has not been the case in Clackamas or Washington Counties, both of which have experienced recent successes at lowering their unsheltered homelessness.

Unsheltered Homeless Per 10,000 Residents

Ending unsheltered homelessness in Portland is not a financial burden; it is a programmatic choice. No responsible leader, public or private, in the face of ever-increasing poor performance, would allow these numbers to continue without pivoting and immediately addressing the crisis Portland is experiencing.

Portland and Multnomah County can immediately set up a network of low-cost, flexible walk-in nighttime emergency shelters to care for every person in our community. Our community safety laws could immediately be enforced, taking the pressure off our overwhelmed public safety resources, and we can begin to repair, restore, and revitalize our community.

2020s

Our Public Safety System is Overwhelmed

We cannot arrest our way out of unsheltered homelessness

Here’s the simple truth: Portland’s unsheltered homeless—less than a single percent (<1%) of our population—are responsible for over 50% of police arrests. It’s unsustainable, and this critical public safety service has been strained to the breaking point.

A decade ago, Portland Police took 6 minutes to respond to a “high” priority call. In 2023, it took 24 minutes. Now, when a Portlander needs assistance in their most critical time, an officer will take four times longer to respond. And in some “medium” and “low” priority calls, they may not respond at all.

*https://www.portland.gov/police/open-data/documents

** https://manhattan.institute/article/portlands-police-staffing-crisis

The rising unsheltered homeless population moves in lockstep with skyrocketing arrests of our unsheltered homelessness, showing we cannot arrest our way out of this humanitarian crisis.

Our public emergency response network (police, fire, ambulance) is overburdened, understaffed, and unsupported. As our law enforcement officials spend a tremendous amount of their time arresting and then releasing the unsheltered, public safety has deteriorated across the city. In recent years, gun violence and vehicular homicides have escalated to near-record levels, and rising property crimes have pushed Portland into one of the top ten most crime-ridden cities in the nation. Our city’s police officers were not hired or trained to deal with the unsheltered homeless on the large scale Portland is currently facing. Its increasing levels make it more challenging to employ, train, and retain an adequately sized police force, further intensifying our public safety crisis.

Ending Unsheltered Homelessness Will Rapidly Improve

Public Safety System Response Times

But what can have a significant effect is shelter. From 2016 to 2019, only 2% of all people arrested lived in shelters. In other words, basic shelter reduced the likelihood of arrest of a sheltered vs. unsheltered person by 96%, freeing up our crucial public safety officers and other resources to respond and care for every community member, both housed and unhoused.

2020s

Try > Fail Fast > Improve > Try Again

With best practices learned, how can Portland add humane, lifesaving sheltering capacity fast and at low cost?

Try >

Brisbane, Australia

Beddown

If we can shelter cars with more dignity than people, what does that say about our society?

In 2018, Norm McGillivray founded Beddown in Brisbane, Australia. Norm knew firsthand the struggles of those sleeping rough on the streets, having lost his father, who was suffering from mental illness and was homeless at the time of his death. This experience and the growing need in his community for those sleeping rough (unsheltered) led him to an innovative idea to immediately provide basic, low-cost lifesaving shelter.

Norm McGillivray – Beddown Founder, Australia Person of the Year Nominee and Shelter Portland Leadership Council member - Pop Up Emergency Shelter providing the 5 S’s (Safety, Security, Services, Shelter, Sleep)

Beddown created pop-up overnight accommodation in carparks sparking interest across the globe, including from the Shelter Portland team. Making these available under-utilized facilities, often with bathrooms and showers, available at night, when the facilities weren’t being used, for people sleeping rough, seemed like a perfect solution. And at $21 per person per night, it also made it a low-cost and immediate solution.

Working with Norm (Shelter Portland Leadership Council member) as an advisor, Shelter Portland approached TriMet senior leadership to ask for the use of their Gateway transit center park and ride. TriMet readily agreed, noting the many tents around their transit centers, safety concerns from their customers, and the resultant falling ridership, all occurring even before the Covid pandemic.

World Homeless Day 2020

Shelter Portland TriMet Gateway Parking Garage Test

TriMet loaned the Gateway Parking Garage

With TriMet ridership falling and with encampments ringing their stations, they want to provide help finding a solution

Did it work? YES! The initial one-person test was a success.

Fail Fast >

After the initial success, Shelter Portland contacted the City/County Joint Office of Homeless Services (JOHS) and Transition Projects, Portland’s largest homeless shelter provider, to recommend a full-scale test.

Four months later, on the coldest winter day, JOHS and Transition Projects set up a severe weather shelter using Beddown’s pop-up shelter concept at the Oregon Metro parking garage on Grand Avenue, with five staff and volunteer members providing tents and sleeping bags to 30 unsheltered homeless persons with two heavy-duty portable heaters working hard to counter the 20-degree temperature, the shelter operated for several days until the severe weather emergency ended.

Did it work in winter? NO!

The guests and volunteers were miserable. In addition, the high cost of modifying the parking garage to withstand winter weather, such as tents, sleeping bags, and portable heaters, made the venture cumbersome to set up, and it could not be readily knocked down to convert the parking garage back to its normal daytime purpose in the winter months.

The tropical temperatures of Brisbane, Australia, make this low-cost solution feasible, whereas the cold and wet winters in Portland make it challenging and more expensive.

Metro parking garage severe winter shelter

Shelter Portland’s Keith Wilson with volunteers at the Oregon Metro parking garage

Portable heaters were used to counter the freezing temperatures

Tents outside Oregon Metro parking garage. When providing outreach to the approximately 15 tents around the parking garage, only one person accepted our offer to come into the warming shelter

Improve >

With 517 churches in Portland, most of them unused at night, Shelter Portland tested a nighttime emergency shelter on World Homeless Day 2021 at the Church of Nazarene, located on Powell Boulevard and Interstate 205.

Shelter Portland, joined by Matt Perkins, a friend experiencing homelessness, set up a nighttime emergency shelter in the church's main congregation area.

World Homeless Day 2021 Shelter Portland’s Keith Wilson and Shelter Now’s Lived Experience Council Member Matt Perkins

Church of Nazarene nighttime emergency shelter test

Did it work? YES! Would it work 365 days a year? YES!

Try Again >

Now, during the winter months, from November to March, United Gospel Mission operates a walk-in nighttime emergency shelter at the Church of Nazarene with limited financial assistance from Shelter Portland.

United Gospel Mission Matt Stein, Shelter Portland Keith Wilson and Matt Huff, UGM Adam Moore

Shelter Information:

-

Hours of operations: Nightly, 9pm to 7am

-

Bed capacity: 45 guests per night

-

Guest to Staff Ratio: 23:1

-

Shelter Portland’s rent payment per month to church (when funds are available): $4,000

-

$16 per person per night

At $16 per night, this walk-in nighttime emergency shelter is less than 10% of the cost of a City of Portland-operated Safe Rest Village, which costs $189 per person per night, or Temporary Alternative Shelter Site.

Can walk-in nighttime emergency shelters scale up capacity quickly? YES!

Shelter Portland Keith Wilson, Matt Huff, and Kristopher Taft setting up a nighttime emergency shelter

This highly flexible sheltering our unsheltered solution can be arranged in as little as a month and can as easily be reduced as the needs of the community rises and falls ensuring no person in Portland must suffer the cruelty and inhumanity of sleeping outside in dangerous and unsanitary conditions on any night of the year.

Proof of the flexibility of this concept occurs every winter.

JOHS Severe Weather Shelters

December 2021

In 2021, from December 25th to January 2nd, temperatures in Portland were below 30 degrees and ice blanketed the Portland region. With thousands of area residents living unsheltered, Multnomah County and Portland, within only a few days, provided the following lifesaving saving resources:

-

7 Facilities providing 670 Beds (Covid severely reduced fire marshal facility capacity)

-

774 volunteers over 9 days

-

105 Neighborhood Emergency Team volunteer members

-

4 Governmental Organizations

-

11 Support organizations

-

4 Volunteer Organizations

-

559 peak population

These facilities, such as community centers and churches, were trauma-informed community assets where many Portlanders spent time with fellow community members.

The Salvation Army Moore Street Community Center Severe Weather Shelter

The Salvation Army Moore Street Community Center Severe Weather Shelter

Entrance to the Moore Street Community Center Severe Weather Shelter

30 years ago in Portland, and common practice in other cities in our nation today, nighttime emergency shelters were used to care for our community members in crisis 365 days a year, not just on the coldest days and nights in winter.

Without our community leaders employing a continuous improvement mindset, ‘try > fail fast > improve > try again,’ we are only left with the failing.

Approximately 400 homeless people are going to die in our community this year. No reasonable person or government should wait to act; they must try, fail fast, improve, and try again. Never rest and try and fail until a solution is found and fully implemented. Our community depends on us.